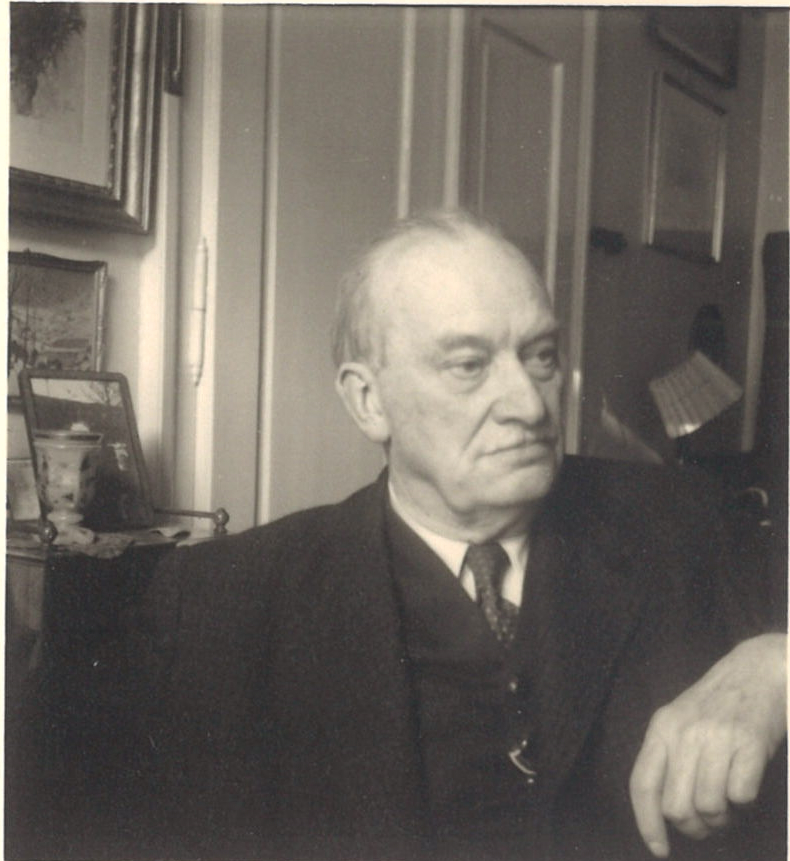

About Franz Nabl

Biography/ Stages of life

Franz Nabl was born on July 16, 1883 in Lautschin/Loučeň (Bohemia) as the son of Franz Nabl, a councillor of the "Thurn und Taxis" estate. After his father's retirement in 1886, the family moved to Vienna. From 1891-1895, Nabl spent his childhood in Baden near Vienna. After private schooling, he attended the grammar school in Baden from 1893 and the Elisabeth Grammar School in Vienna from 1895-1900. He returned to Baden from 1900-1902 and passed his school-leaving examination in 1902. From 1902-1907 he studied law for four semesters and then philosophy in Vienna. In 1907 he married Hermenegild Lampa and broke off his studies. In the meantime, he moved to Enzesfeld an der Triesting, was back in Vienna from 1911-1913 and in Baden from 1913-1924. From 1924-1927 he worked as a feature editor for the "Neues Grazer Tagblatt" in Graz. In 1927 he returned to Baden for a few years, but then lived in Graz for good from 1934 onwards. After the death of his first wife in July 1937, he married Ilse Meltzer in March 1940. Franz Nabl died in Graz on January 19, 1974 as the doyen of (traditional) Styrian literature.

Political orientation

In the 1920s, Nabl increasingly aligned himself with the anti-urban, nationalist camp and frequented the corresponding (literary) circles in Graz ("Südmarkrunde"). In 1933, together with many other Austrian authors from the nationalist camp, he demonstratively resigned from the Austrian P.E.N. Club and from 1936 was a member of the "Bund deutscher Schriftsteller Österreichs" (Association of German Writers in Austria), which acted as a Nazi front organization and information carrier for the Third Reich. After the "Anschluss", Nabl used the esteem in which he was held by the new rulers and librarians (Erwin Ackerknecht) and literary scholars (Ernst Alker) for "reading trips" and poetry meetings in the "old Reich" and was open to honors and prizes (1938 "Mozart Prize" from the Hamburg Goethe Foundation, 1943 honorary doctorate from the University of Graz). Unlike other authors such as Hans Kloepfer, there is no evidence that he wrote poems of homage to the Führer or publicly advocated the Nazi regime. Despite his own self-assessment as "apolitical", the author must nevertheless be regarded as a somewhat opportunistic beneficiary of the Nazi system, who even after 1945 found no clear words about (his own) Nazi involvement.

A detailed, critical and balanced account of Nabl's relationship to politics in general and to National Socialism in particular can be found in Klaus Amann: Franz Nabl - Politischer Dichter wider Willen? Ein Kapitel Rezeptions- und Wirkungsgeschichte. In: Über Franz Nabl. Aufsätze. Essays. Reden. Hrsg. v. Kurt Bartsch, Gerhard Melzer und Johann Strutz. Graz/Wien/Köln: Styria 1980, pp. 115-142.

Work and impact

In his novel Der Ödhof, published in 1911, Nabl incorporated a great deal of autobiographical material - from his problematic relationship with his distant, authoritarian father to his home and experiences at the "Gstettenhof" near Türnitz in Lower Austria, which was owned by the Nabl family from 1888 to 1901 as the real historical model for the Ödhof. The upper middle-class origins with their appeals to efficiency and rigid behavioral norms, the traumatic childhood experiences of dependency and lack of justification for life, the relationship with the feminine that fluctuates between fascination and revulsion - all these factors combine to create a family and social tableau in the tradition of realistic storytelling that focuses on the individual development (and failure) of individual characters. The catalog of values conveyed ranges from obvious prejudices and ideologizations (women, social democrats, the "rabble") to tolerance towards marginalized groups and outsiders (Jews, alcoholics, foreigners) and bourgeois-liberal attitudes towards religion and marriage. Characteristic of Nabl's "lifelong dichotomy" (Peter Handke) is the contrast between the longing for freedom and self-discipline, between vastness and narrowness, escape and confinement.

In 1917, the novel Das Grab des Lebendigen (later published under the title Die Ortliebschen Frauen) was published for the first time. It describes the life of the lower middle-class Ortlieb family, who, after the death of the head of the household, increasingly shut themselves off from the outside world and devote themselves exclusively to meticulous, frugal housekeeping in their everyday activities. Possible changes create fear: daughter Josefine in particular nips any attempt at contact by siblings Anna and Walter in the bud, finally even locks her beloved brother in the cellar and commits suicide when he is freed.

The novel, which was made into a film by Luc Bondy in 1979, later attracted the interest of prominent contemporary authors. After Elias Canetti, Martin Walser in particular championed Franz Nabl and his work: "One would like to ask literary historians to investigate why this book is not mentioned every time the great books in the German language are mentioned," said Walser in 1994 when accepting the Franz Nabl Prize of the City of Graz.

Shortly before his death in 1974, Nabl's rejection of the idyll of traditional Heimat literature also made him interesting for the young, up-and-coming authors of the "Forum Stadtpark": Peter Handke, Alfred Kolleritsch and Gerhard Roth appreciated Nabl's austere narrative form, which focuses above all on the - often failing - self-determination of adolescents. The name Nabl, which apparently signaled the power of integration, seemed ideally suited to Styrian cultural policy to name prizes and institutions after this author: the Franz Nabl Prize of the City of Graz, first awarded in 1975, or the Franz Nabl Department for Literary Research, opened in 1990, which from the outset, however, did not focus its activities on the name giver, but on Styrian (contemporary) literature in general. Particularly in the wake of the Nabl Prize award ceremonies, discussions sometimes arise about the person of Nabl and the political problems of naming the prize - for example, the 2003 winner, Norbert Gstrein, suggested renaming the prize the "Miroslav Krleža and Ivo Andric Prize" in his acceptance speech. The "sparring partner" of the now nationally known trademark "Franz Nabl" has always been a source of controversy and historical analysis, even if - as with street names - the name has lost its semantic charge over time and mutated into an almost neutral container for the activities or services offered by the institutions and for which they stand.

Gerhard Fuchs